Facts Aren’t Enough: 4 Surprising Truths About How We Process Truth

06 Feb. 2026 /Mpelembe Media — President Donald Trump ignited a “viral racism controversy” by sharing a video on Truth Social that depicted former President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama as apes. The 62-second clip, set to the song “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” featured debunked claims regarding 2020 voter fraud in Michigan and included caricatures of other Democrats—such as Joe Biden and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—as animals.

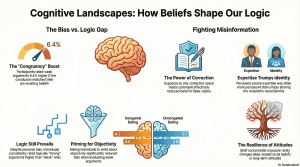

We were promised that the “Information Age” would be an era of enlightened consensus. Instead, we find ourselves in a fractured reality where two people can stand on the same street corner, look at the same set of facts, and walk away with diametrically opposite versions of the truth. It is tempting to write this off as a simple lack of intelligence or an absence of shared information, but the reality is far more sophisticated.We do not merely receive information; we navigate it. Our minds operate within “Cognitive Landscapes”—internal terrains shaped by identity, emotion, and pre-existing beliefs that act as a high-resolution filter for every claim we encounter. Recent behavioral research suggests that our “stubbornness” isn’t a failure of logic, but a feature of how our brains protect our worldview. To understand why facts alone fail to move the needle, we must look at four surprising truths about the mechanics of our modern belief systems.

1. The “Logic Trap”: Why We Forgive Bad Reasoning

It is a comforting myth that humans are simply bad at logic. In reality, we are quite capable of distinguishing a sturdy, evidence-based argument from a flimsy one. The problem is that we are willing to “look the other way” if the conclusion makes us feel good. Social scientists call this the Argument Congruency Bias—a psychological blind spot where we favor arguments that align with our pre-existing beliefs, regardless of their logical integrity.The data reveals a striking double standard: we are 12% more likely to rate a strong argument highly if it reaches a conclusion we already like. Even more dangerously, we often use factual premises to justify a “logic leap.” Consider the Democratic Peace Theory: the observation that democracies rarely go to war with one another. A biased observer might conclude that “because any country not currently at war must be a democracy.” This is the classic fallacy of “affirming the consequent.” We take a true fact and use it to prop up a flawed conclusion because it fits our preferred narrative. Essentially, if we agree with the “where,” we stop caring about the “how.”

2. The “Objectivity Prime”: Writing Your Way to Fairer Thinking

If our biases are automatic—a “knee-jerk” emotional response—can we actually train ourselves to be more impartial? The answer is yes, but it requires more than just a passing desire to be fair.In a series of experiments, researchers tested an “Objectivity Intervention.” In the first study, participants were asked to engage in “automatic goal pursuit” by actually writing a short paragraph on why objectivity was valuable to them personally and to society at large. This simple act of articulation reduced bias toward weak arguments by roughly 5%.However, there is a catch. When a second study tried a “passive” version—merely asking people to rate how much they agreed with statements about being objective—the effect vanished. The “magic ingredient” for clearer thinking is active engagement. We cannot just read about being fair; we have to physically and mentally articulate the goal to trigger our brain’s analytical systems. One participant captured the essence of this mindset perfectly:”Objectivity is important… because it’s important to think about many sides of an issue, and not just your own. It’s OK to disagree… but it’s important to have informed opinions about issues that are important to society as a whole.”

3. The Identity Paradox: When Expertise Beats Shared Identity

There is a common assumption in political communication that the “messenger is the message”—that to change a mind, you need a source from the same “in-group.” But recent research into culturally-relevant corrections suggests a more nuanced “Identity Paradox.”Imagine Maria, a 32-year-old Latina in Los Angeles, scrolling through her feed and seeing a post claiming that ICE agents are arresting people at her local polling station. The fear is visceral, and she considers staying home. Traditional wisdom says Maria will only listen to a correction if it comes from a fellow Latino organization. But while corrections from groups like UnidosUS or the NAACP were effective, they weren’t significantly more effective than generic sources.The data suggests that perceived expertise and authority often carry more weight than shared racial identity. In fact, a fascinating “out-group” effect occurred: White participants actually placed more trust in the NAACP than in generic sources when it came to issues specifically affecting Black communities. We don’t just look for people who look like us; we look for the people we believe are the most credible authorities on the specific threat at hand.

4. The Resilience of Belief: Social Media’s Limited Reach

In an era of digital activism and “cancel culture,” we often hope that the sheer volume of digital discourse can shift the needle on deep-seated societal attitudes. However, a massive study of 3,500 participants exposed to endorsements or condemnations of racial slurs found a “notable resilience” in racial attitudes. Brief digital interactions—the “noise” of our social media feeds—rarely shift the bedrock of our beliefs.Why are these views so stubborn? It is largely because racial norms have evolved from “old-school” biological racism into what sociologists call “symbolic racism.” Instead of direct attacks, modern prejudice often uses “dog whistle” politics and coded language—critiquing “cultural deficiencies” rather than inherent traits. This makes beliefs much harder to dislodge because they are woven into a complex web of social identity and cultural narrative. As the research notes, “deeply entrenched beliefs… are resistant to immediate influence through digital discourse.” We aren’t just protecting an opinion; we are protecting a lifetime of social conditioning.

The Final Thought: Navigating the Fortress

The overarching reality of these findings is that our brains are not passive receivers of information; they are active, defensive navigators. We don’t just “see” the truth; we interpret it to fit the map we’ve already drawn.If brief fact-checks and the digital roar of social media are not enough to dismantle our cognitive fortresses, we must ask ourselves a more demanding question: Are we building social platforms for genuine connection, or merely for the reinforcement of our own cognitive strongholds?The silver lining is that the ability to recognize strong logic still exists within us. We aren’t incapable of being objective; we are just out of practice. The path forward may not lie in the mere delivery of more facts, but in finding ways to force ourselves out of the “passive” mode of consumption and back into the active, difficult work of thinking for ourselves.