The Erotics of the Knee and the Victorian King: Decolonizing Zambia’s “Bird-Like” Silhouette

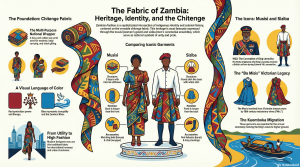

10 Feb. 2026 /Mpelembe Media — In the heart of Southern Africa, the visual landscape is a moving gallery of saturated color and structural complexity. To the casual observer, the vibrant fabrics draped across shoulders or swaying in the heat of the Bulozi Plain are simply striking textiles. However, through a cultural lens, the Chitenge and the traditional Lozi attire are much more: they are “living monuments.” In Zambia, clothing is a sophisticated system of social signifiers that unifies the Lozi—a people composed of 38 distinct ethnic groups—into a singular national identity. From the “sartorial engineering” of the heavy skirts to the global journey of the wax prints, Zambian fashion narrating a story of indigenous resilience, colonial appropriation, and a confident modern renaissance.

The Siziba attire itself is essentially a reconstructed military uniform, and aside from the red beret (lishushu), the other primary military accents found in the traditional regalia are the white shirt and long stockings.

The White Shirt and Stockings: The Siziba ensemble is not just a wrap; it traditionally incorporates a crisp white dress shirt and long stockings. These specific elements were adopted directly to replicate the formal aesthetic of the British military uniform (specifically King Edward VII’s uniform) that was gifted to King Lewanika in 1902.

The “Uniform” Silhouette: The entire ensemble is designed to function as a “uniform” of dignity. While the lower half (the siziba cloth) adapts the look into a skirt-like African silhouette, the upper half—comprising the white shirt, stockings, and beret—serves to emulate the regimented appearance of the British officer class from the Edwardian era.

It is worth noting that while the men’s attire (Siziba) draws from military history, the women’s attire (Musisi) draws from Victorian civilian fashion (specifically the dresses worn by missionary wives, or “Bo Misis”), creating a distinct gendered split in the colonial influences on Lozi regalia.

The Siziba attire carries deep historical roots and cultural weight in Zambia, evolving from a symbol of royalty to a broad representation of national identity.

Origins and Traditional Use The Siziba originated in the Lozi Kingdom of Western Zambia. Historically, this attire was reserved for royals and dignitaries to wear during significant ceremonial events. A primary example of its traditional use is the Kuomboka festival, an annual event that celebrates the end of the rainy season.

Symbolism and Design The attire is crafted from chitenge, a durable and versatile cotton fabric. The designs and colors of the Siziba are not merely decorative but carry specific cultural meanings regarding social status, strength, and peace:

Red: Symbolizes power.

Blue: Represents tranquillity.

White: Signifies peace.

Intricate Designs: These patterns narrate stories of strength and social standing.

Modern Cultural Significance While it remains a “testament to Zambia’s rich culture and history,” the significance of the Siziba has expanded beyond its Lozi origins.

National Identity: The attire has been adopted by Zambians across various regions and ethnic groups, transforming it into a unifying symbol of national identity.

Fashion: It has been successfully incorporated into modern fashion trends, transcending its traditional roots to appeal to contemporary sensibilities.

Gendered Usage: In contemporary practice, men typically wear the Siziba, while women wear a corresponding attire called the Musisi, often accompanied by elegant headpieces.

Recent Prominence The cultural profile of the Siziba was recently elevated due to a friendly social media exchange between Zambians and Ghanaians. Sparked by a visit from former Ghanaian President John Mahama, a playful debate arose comparing the Siziba to the Ghanaian fugu (smock). This interaction highlighted the “rich diversity of African traditions” and reinforced the Siziba’s status as a point of pride for Zambians.

Based on the sources, the Kuomboka festival served as a primary arena for establishing the traditional exclusivity and prestige of the Siziba attire.

Context of Usage: The Siziba is originally from the Lozi Kingdom in Western Zambia. The Kuomboka festival, which celebrates the end of the rainy season, was the key ceremonial setting for this attire.

Status Symbol: During the festival, the Siziba was strictly reserved for royals and dignitaries. This usage reinforced the garment’s association with high social status and power before it later evolved into a national symbol worn by the wider public.

Would you like me to create a slide deck that visually summarizes the history of the Siziba, its transition from royal attire to national fashion, and the recent “fashion diplomacy” with Ghana?

The Musisi’s distinctive, bell-like silhouette is an architectural feat of tailoring that relies on a specific layering system and reinforcement materials to maintain its volume.

Three-Layer System: The garment typically consists of three primary layers: two inner skirts that build initial volume and a heavy outer layer that defines the final form.

Integrated Stiffener: To prevent the fabric from draping flat against the body, a “stiffener” is integrated directly into the top layer. This reinforcement provides the structural integrity necessary for the garment to hold its rigid, flared shape.

Victorian Influence: This method of construction mirrors the engineering of late 19th-century crinolines and bustles, reflecting the garment’s historical evolution from Victorian dress styles.

Material Consumption: This design is famously labor-intensive and “gobbles up” vast amounts of fabric. The flared shape is often supported by using heavy-weight fabrics like satin or chitenge (cotton wax print), which are durable enough to carry the weight of the stiffeners and multiple layers.

The asymmetric hemline in Lozi attire is a deliberate design element that serves both aesthetic and functional purposes, distinct to each gender.

For Women (Musisi) The Musisi is constructed with the back of the skirt longer than the front. This architectural choice is designed to create a specific graceful “swing” when the wearer walks. This rhythmic movement is not merely decorative but is a display of poise and traditional training, reflecting proper Lozi etiquette. The design historically mirrors the influence of late 19th-century Victorian bustles, which added volume to the back of the dress.

For Men (Siziba) The Siziba features an inverse hemline logic, where the front of the skirt-like base is longer than the back. This distinguishes the male garment from the female Musisi and contributes to the attire’s unique silhouette, often described as being “elegantly worn like a bird”.

Would you like to explore how these designs are being adapted by modern fashion designers in Zambia?

Based on the sources, the asymmetric hemline design in Lozi attire dictates specific movement patterns and postures for both men and women, turning the act of walking into a display of cultural etiquette.

The Musisi: The Rhythmic Swing For women, the Musisi is constructed with the back of the skirt longer than the front. This structural imbalance is not accidental; it is engineered to create a specific physical effect:

The “Swing”: The extra weight and length at the back force the heavy, multi-layered skirt to oscillate rhythmically as the wearer moves.

Poise and Training: To achieve this graceful “swing,” a woman must adopt a deliberate gait. This movement is a learned skill and a display of poise and traditional training, reflecting proper Lozi etiquette.

The Siziba: The Bird-Like Elegance The Siziba worn by men features an inverse hemline, where the front of the skirt-like base is longer than the back. This design influences the male bearing in different ways:

“Worn Like a Bird”: This silhouette contributes to the description of the attire being “elegantly worn like a bird”.

Functional Looseness: The garment is designed to sit loosely on the body, allowing for the ease of movement required for traditional duties, such as the energetic paddling and dancing performed during the Kuomboka festival. The movement of men in Siziba is often intended to evoke the grace of the waterfowl found in the Barotse Floodplain.

King Lewanika’s 1902 visit to England to attend the coronation of King Edward VII was a watershed moment that directly redefined Lozi men’s fashion, specifically birthing the Siziba attire.

The Catalyst: A Royal Uniform During his visit to London, King Lewanika was gifted a British military-style uniform (often referred to as King Edward’s uniform) as a gesture of respect. Upon his return to Barotseland (Western Zambia), the Lozi people sought to emulate their monarch’s new, dignified appearance and identify themselves with his prestige.

The Transformation of Attire This desire to mimic the King’s British regalia led to the creation of the Siziba, a “uniform” that blends Edwardian military aesthetics with indigenous design:

European Elements: To replicate the formal look of the British uniform, the Siziba incorporated a crisp white shirt and long stockings.

Military Accents: The ensemble often includes a red beret, known as a lishushu or mashashu, adding a final military-inspired touch to the outfit.

African Silhouette: While the top half mimics a uniform, the bottom half was adapted into a flared, skirt-like base. Uniquely, the Siziba features an inverse hemline where the front is longer than the back, creating a silhouette often described as “elegantly worn like a bird”.

Cultural Shift Prior to this era, Lozi dress primarily consisted of animal skins (liiba). The 1902 visit accelerated a shift toward imported fabrics like satin and later chitenge, transforming the attire from functional tribal wear into a symbol of “dignity value” and national unity.

The lishushu (also known as mashashu) is a red beret that serves as a mandatory component of the Siziba ensemble for formal occasions, acting as a visible signal of the wearer’s commitment to civic duty and traditional protocol.

Symbol of Protocol: The beret is not merely decorative; its presence is required for formal protocol. Wearing it signifies the individual’s adherence to the established norms of Barotse masculinity and their respect for the social hierarchy.

Military Heritage: The lishushu adds the final touch to the Siziba’s military-inspired aesthetic. This design element traces back to 1902, when King Lewanika adopted a British military uniform (King Edward’s uniform) as a symbol of prestige, which the Lozi people subsequently emulated.

Completing the Ensemble: It is worn alongside the crisp white shirt, the skirt-like siziba base, and long stockings, completing the transformation of the wearer into a figure of “dignity value”.

Would you like to explore how modern designers are reimagining these specific military elements in contemporary fashion collections?

Based on the sources, the Siziba attire itself is essentially a reconstructed military uniform, and aside from the red beret (lishushu), the other primary military accents found in the traditional regalia are the white shirt and long stockings.

The White Shirt and Stockings: The Siziba ensemble is not just a wrap; it traditionally incorporates a crisp white dress shirt and long stockings. These specific elements were adopted directly to replicate the formal aesthetic of the British military uniform (specifically King Edward VII’s uniform) that was gifted to King Lewanika in 1902.

The “Uniform” Silhouette: The entire ensemble is designed to function as a “uniform” of dignity. While the lower half (the siziba cloth) adapts the look into a skirt-like African silhouette, the upper half—comprising the white shirt, stockings, and beret—serves to emulate the regimented appearance of the British officer class from the Edwardian era.

It is worth noting that while the men’s attire (Siziba) draws from military history, the women’s attire (Musisi) draws from Victorian civilian fashion (specifically the dresses worn by missionary wives, or “Bo Misis”), creating a distinct gendered split in the colonial influences on Lozi regalia.