John Hammond, University of Reading and Yiorgos Gadanakis, University of Reading

Welcome to this special report on the food industry, the fourth instalment in our series on where the global economy is heading in 2023. It follows recent articles on inflation, energy and the cost of living.

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, the closely watched food price index of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reached its highest recorded level, stoking consumer prices across the world. In the UK, for example, the prices of many everyday items increased way ahead of inflation, with bread and eggs both up 18% in the year to December, and milk up 30%.

Such rises threatened food security, particularly in low and middle-income countries that rely heavily on Ukraine and Russia for grains and plant oils. That included many countries in Africa and Asia, which took 95% of Ukraine’s wheat exports in 2021 (roughly a tenth of the world supply).

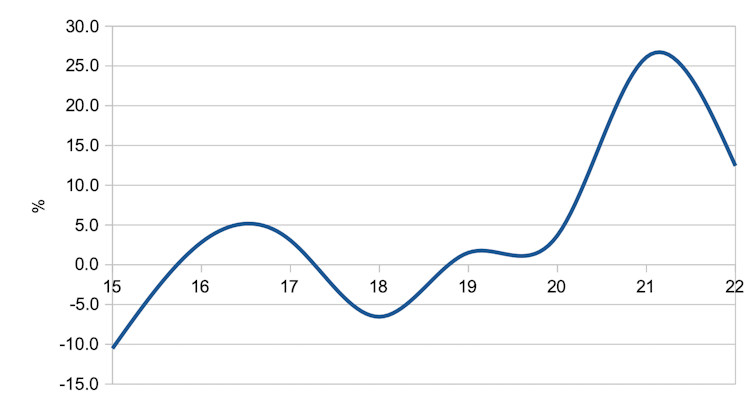

Global food price inflation

This prompted much talk in the media about the potential for famine. Yet nearly a year after the invasion, the FAO food price index has returned to pre-invasion levels.

So why has pressure on prices reduced, and what are the prospects for the year ahead?

What happened in practice

You can’t look at food in isolation from COVID. Many people in the energy and food industries were either too ill to work or prevented from doing so because of pandemic restrictions, which squeezed supplies. When the world opened up and demand began to rise, food and energy prices went up too.

This made people particularly vulnerable to events in Ukraine. Once the war began, food-price inflation peaked because the markets were uncertain about whether production and exports would be hit, and how global supply chains would adapt.

Ukraine’s grain exports resumed after a UN deal was brokered in July to create a humanitarian corridor through the Black Sea. It also helped that the wheat harvest was larger than expected, even if large areas around the front line remain unharvested. Much of Ukraine’s corn has not been harvested either, for the additional reason that the drying process is energy intensive and farmers struggled to afford the raised prices. Overall, Ukraine’s grain exports were down in 2022 by about 30% year on year.

Russia is normally an even bigger exporter of wheat than Ukraine, supplying about 15% of world demand. It’s harder to see what has happened to these supplies because the Russians stopped providing data, but certainly Moscow’s policy of only dealing with “friendly” countries will have affected availability for many countries too.

Countries that rely heavily on Ukrainian/Russian grains have been forced to shop elsewhere. For example Yemen and Egypt have imported more grain from India and the EU, paying higher prices than usual.

Several additional pressures on farmers have further squeezed the global food supply. Fertiliser prices have rocketed in the past two years. Russia, an important global supplier, has been stockpiling for domestic use. Elsewhere, heightened energy prices have squeezed output. In the UK, the largest nitrogen-fertiliser facility suspended production during 2022. Average fertiliser prices for UK farmers are now 18% higher than the winter before the Ukraine invasion, and 66% higher than two years ago.

Extreme weather in summer 2022 was another problem, including heatwaves and drought in northern Europe, America and China, flooding in Pakistan and drought in Argentina. Irrigation has become more difficult in areas that depend on it, while in Europe drought conditions have reduced the supply of crops for animal feed and harvest of grass for silage. Meat and vegetable prices have both gone up as a result.

According to the UN’s World Food Programme, the overall effect of inflation, war and extreme weather has been that many people around the world have had their access to food restricted. The number of people facing severe food insecurity is up 20% since the war began.

The outlook

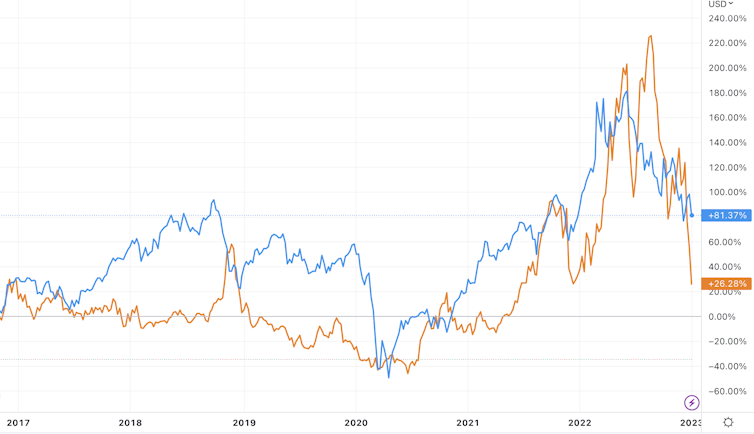

Wholesale gas and oil prices have at least declined from their 2022 highs, which will benefit the entire food supply chain. This is one reason why inflation eased slightly in the autumn in many countries.

Oil and gas prices

Trading View

This will have taken some of the heat out of the global food price index. Cereals, meats and particularly vegetable oil prices all fell towards the end of the year, though sugar and dairy prices went in the opposite direction. Overall food price inflation remains historically high.

For the year ahead, the area of crops planted in Ukraine is estimated to be 17% down on 2022. Farmers in other countries are planting more wheat and maize to compensate, though the overall supply will still be pressured by higher farming costs and potentially more extreme weather.

Fertiliser prices will probably stay high as supplies remain restricted. Farmers in wealthier countries may keep applying normal quantities to their crops, like on previous periods of raised prices. But in poorer countries they may cut back, threatening yields and quality and exposing smallholder communities to greater food insecurity.

Stockr

In sum, many staples will likely remain in tight supply in 2023, meaning price pressures continue. Retailers will be forced to either absorb the costs or pass them on to consumers. Governments will have to consider how to both support struggling consumers but also farmers to maximise what they produce.

At the international level, there needs to be an urgent fertiliser supply agreement to minimise disruptions, prioritising access for vulnerable communities in developing countries. Longer term, farming needs to reduce its dependency on fertilisers by developing agricultural practices that optimise the cycling of nutrients.

This includes more efficient use of manures and extracting nutrients from sewage, and using more legume crops in rotations to take advantage of the fact that they enhance nutrients in the soil. There also needs to be more precision farming techniques to target resources within fields to where they will be used most efficiently.

These practices are well adopted in western countries, but other parts of the world lag behind – particularly developing countries. Fertilisers will always be part of the farming system, but we’ll make food production more sustainable if we can get these things right.

This article is part of Global Economy 2023, our series about the challenges facing the world in the year ahead. You might also like our Global Economy Newsletter, which you can subscribe to here.![]()

John Hammond, Professor of Crop Science, University of Reading and Yiorgos Gadanakis, Associate Professor of Agricultural Business Management, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.