Piers Forster, University of Leeds

The UK’s Climate Change Committee – the official independent advisory body of which I am interim chair – has spent the past three months poring over thousands of pages of government strategy documents to inform its latest annual progress report to parliament. And our confidence in the UK meeting its climate goals is now markedly less than it was in our previous assessment a year ago. Key opportunities have been missed.

Before the COP27 Glasgow climate summit in 2021, the UK committed to reduce emissions by 68% by 2030. Every country that signed the Paris Agreement set a pledge – and this was the UK’s. If the country is to deliver it in only seven years, the rate of annual emissions reduction outside the electricity supply sector must nearly quadruple, increasing from its current value of 1.2% per year to 4.5% per year. Every year that the government fails to up the pace, it becomes harder the next year – and the scale by which action needs to multiply becomes larger.

Even in the electricity supply sector, which has seen wind power surge and coal collapse, there is a lack of overall strategy to decarbonise the electricity grid and progress is being stymied by planning bottlenecks over building key bits of infrastructure. Other sectors are still way off target.

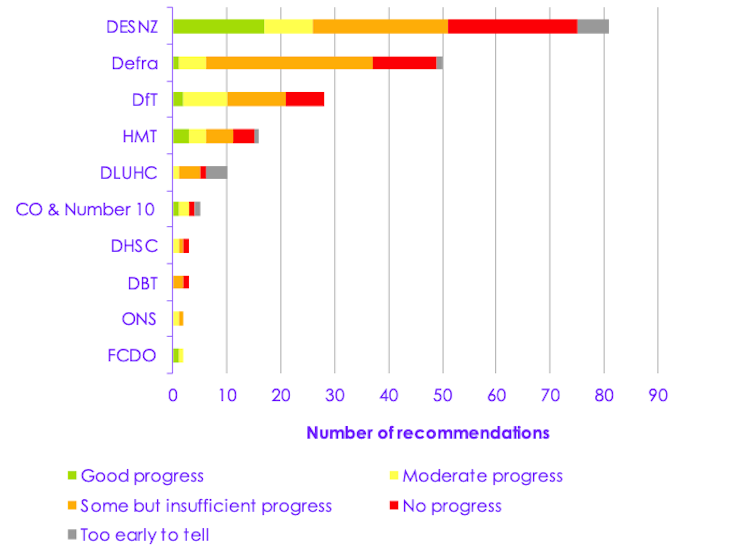

CCC 2023 Progress Report, CC BY-SA

The UK is not giving its industries the support they need to electrify and decarbonise and there is little sign of progress. The government has set a laudable ambition to decarbonise steel and develop carbon dioxide removal industries but there are few concrete plans in place.

While the US, EU and China invested billions in green industries to help the energy and cost of living crises, the UK has so far failed to do the same. This risks losing green jobs and industries to overseas competitors.

The government also needs to focus on developing skills across the workforce – a net zero economy will need many more heat pump installers, foresters and engineers in specific new green technologies. It will launch a workforce action plan early in 2024, which needs to clearly show how skills will be developed within different sectors and across regions.

Joe Dunckley / shutterstock

The farming and land use sector has not seen emissions reduce for more than a decade. Here the government failed to make any of the CCC’s priority recommendations from last year. Tree planting rates need to at least double to meet the government’s own targets and peat restoration rates need to increase by a factor of five. The government has not set out plans for a comprehensive land-use strategy or said how it will support healthier more sustainable diets.

Hero to zero

It is important to reflect on the reason why the UK must act responsibly. There’s “doing our bit”. There’s the need to consider the benefits the UK has had from emissions used in the past. But there’s also a fact that Britain remains a cultural and political leader – a country that punches way above its weight on the international scene. What it does matters. And despite its previous clear direction, the UK has recently sent confusing signals on its climate priorities.

It has gone from leading the world with its net zero commitment back in 2019, to showing support for new oil and gas and consenting to a new coal mine. It’s gone from hosting one of the most successful UN climate conferences ever, to undermining that legacy by risking delivery of its own commitments. This government has taken its foot off the throttle and the world has noticed.

Kevin Shipp / Shutterstock

Glimmers of transition

Our report isn’t all bad news. Glimmers of the net zero transition can be seen in growing sales of new electric cars and the continued deployment of renewable energy generation, but the scale up of action overall is worryingly slow. There seems to be a sense that this can wait until other crises have been dealt with. But many of the crises we are facing – such as the war in Ukraine, the cost of living here in the UK – are interconnected.

The answer isn’t dramatic or drastic (yet) – it’s about delivery and planning and step by step progress. It’s about reporting and transparency and learning from examples – both here and abroad. It’s all very achievable and the CCC has laid out some clear steps – department by department, sector by sector – that can be taken.

For the past 11 years, the Climate Change Committee has been led by John Gummer, Lord Deben. No one could have given more, for longer. It is no coincidence that he has been in post while a net zero target was brought into law and ambitious 2030 and 2035 emission reduction targets were set. Using evidence and political nous he has helped achieve strong cross-party support for climate policies. While he steps down this year, the CCC will continue to channel his spirit and his zeal – his tireless commitment has been an example to us all.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Piers Forster, Professor of Physical Climate Change; Director of the Priestley International Centre for Climate, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.