- Tech education taken to South Africa’s townships

- WiFi access and apps could boost informal economy

- But technology alone is not the answer, experts warn

By Kim Harrisberg

JOHANNESBURG, Sept 1 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Moss Marakalala was 11 when he first used a laptop at an after-school programme in Johannesburg, sparking an interest in technology that inspired him to provide young people like himself from South African townships with digital education.

Today, the 21-year-old runs a production company with his brother and tutors students from townships – deprived, urban areas formed under the apartheid government for people of colour – to become more tech-savvy and enhance their job prospects.

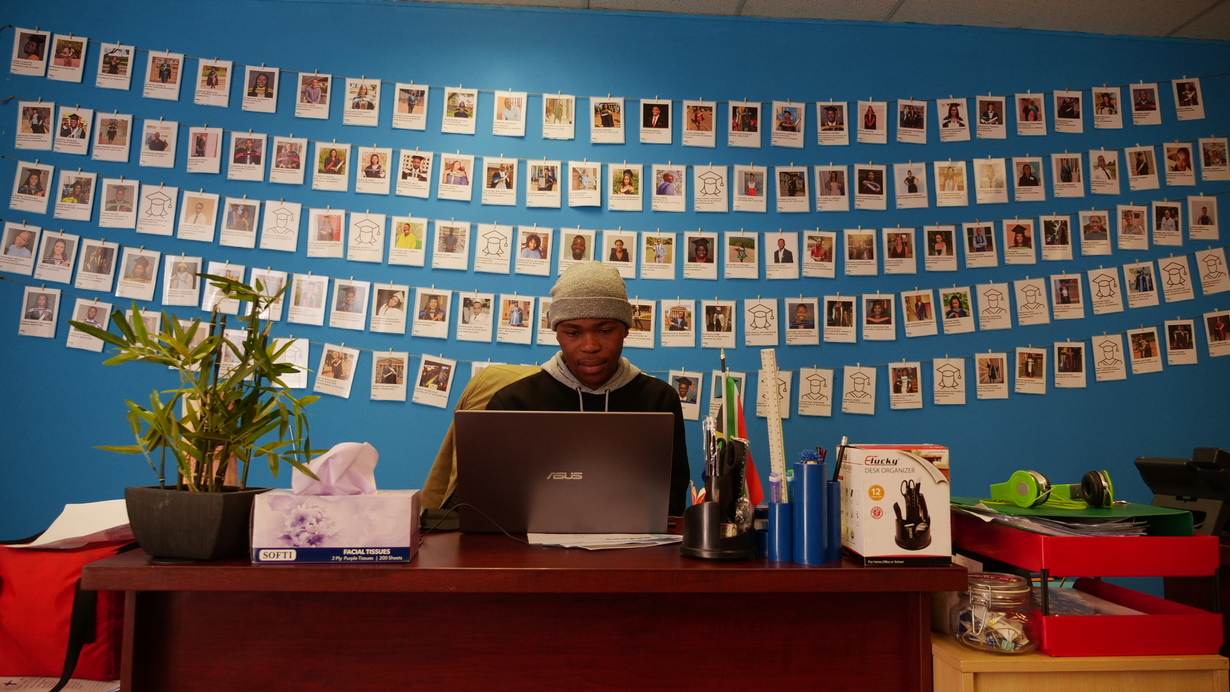

“I feel like tutoring helps me open up a world for others, because IT can create opportunities,” Marakalala said in Johannesburg at the office of Tomorrow Trust, the charity that introduced him to technology and where he now teaches others.

With apps that help detect breast cancer or facilitate business for informal traders, entrepreneurs and charities are striving to ensure the poorest are connected in a country marked by severe power cuts, expensive internet and extreme inequality.

The so-called “digital divide” – the gap between those who have access to technology and the internet and those who do not – is of rising concern to tech experts in African nations, which have some of the world’s lowest internet connectivity rates.

This divide is particularly stark in South African townships, which are typically underdeveloped and neglected areas with high rates of poverty, unemployment and crime.

For many of the country’s poorest citizens, internet access is still a luxury, said Johan Steyn, chair of the artificial intelligence and robotics interest group at the Institute of Information Technology Professionals South Africa.

“We should utilise smart technology platforms to help others achieve a better life, however technology is not the answer by itself,” he said, adding that the government and public also need to address wider social issues such as hunger and crime.

TECH EDUCATION

The South African Tomorrow Trust charity provides orphans and vulnerable children with educational and psychosocial support, as well as feeding programmes.

In 2019, the charity decided it also had to include digital education.

“It’s only fair that every person in this country has got a fair chance at success, right? Because it would be such an injustice if somebody was not exposed to knowing the basics of computers,” said Taryn Rae, its chief executive officer.

The charity has trained at least 350 students from townships on computer basics, from creating an email address and using the video call platform Zoom to coding and robotics training.

The rollout of its tech programme was perfectly timed.

When the country imposed a COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, hundreds of students were able to keep learning remotely using laptops and data packages supplied by the charity.

“We saw students connecting and helping one another out with tech learning online, it was awesome to see,” said Marakalala, who hails from the Thembisa township near Johannesburg.

About half of these students are now considering jobs in the IT sector, according to Rae.

“Before, everyone said they wanted to be a doctor or a lawyer. But now they are thinking about the tech industry so we are equipping them for jobs of the future,” she said.

INFORMAL ECONOMY

While the Tomorrow Trust looks to increase digital literacy, other organisations are striving to improve internet access.

The non-profit Project Isizwe aims to bring affordable public WiFi internet to poor communities across South Africa, including townships, and has reached more than 1.8 million people since 2013.

In partnership with funders, private companies and the government, Project Isizwe builds WiFi zones with hardware that connects directly to internet service providers (ISPs), bypassing costly internet infrastructure.

Local government and donors sponsor the infrastructure and data costs, allowing “WiFi entrepreneurs” from low-income areas to sell affordable WiFi and make a profit on each sale.

Tech entrepreneur Brian Makwaiba said he believed bringing internet access and digital opportunities into townships will help create jobs in a nation where about one in three are unemployed.

In 2017, Makwaiba founded the Vuleka app, which aggregates orders from informal business owners to place bulk orders from manufacturers at reduced costs, and then distribute the products – such as soaps, sugar and rice – directly to the vendors.

About 6,000 traders place 50 daily orders on average through the Vuleka app and it helps them build a credit score in order to eventually take out bank loans.

“Informal business owners can’t be left behind,” said Makwaiba. “If we don’t digitise this space, we risk not being able to sustain our economy.”

HOLISTIC SOLUTIONS

Tech experts say that as well as townships, South Africa’s rural areas risk missing out on technological advancements.

Pretoria-based radiographer Kathryn Malherbe saw this firsthand when breast cancer patients from rural or poor areas arrived for treatment when it was too late to help them, spurring her to invent a mobile app called Breast AI.

The app uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to compare breast scans – sent to a laptop, computer, tablet or smartphone from a wireless ultrasound probe – to thousands of other scans to detect any abnormalities.

These scans are then sent on to the nearest hospital or clinic where patients can receive treatment.

The company is now in talks with major healthcare firms to roll out the software nationwide and hopes to use the algorithm to help with other health issues such as wound treatment.

The app could help the one in 26 South African women who are at risk of developing breast cancer, but tech solutions need to be backed up by education, said Malherbe, who also runs a charity that teaches people about cancer diagnosis and care.

In a country with an array of human rights issues from high crime rates to gender-based violence, tech education and access are sometimes viewed as less urgent matters to address, said Rae of the Tomorrow Trust. But she says this should not be the case.

“Everyone deserves access to what tech has the potential to solve,” said Rae.

(Reporting by Kim Harrisberg @KimHarrisberg; Editing by Kieran Guilbert. Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)