Carol Richardson, The University of Edinburgh

Before news of his hospitalisation for a respiratory infection this week, a fake image of Pope Francis wearing a Balenciaga-style white puffer jacket was posted to Reddit and Twitter. The image – created through AI programme Midjourney – had many viewers fooled into believing that the head of the Catholic church had dramatically updated his style.

As an art historian and an ecclesiastical historian, the image has fascinated me, not least in thinking about the rich history of papal fashion.

First of all, it caught my eye because it looks like shot silk (fabric made of silk woven from two or more colours producing an iridescent appearance). Intentionally or not, it’s a nice nod to the fascia, a sash worn by clerics over their cassocks.

This detail hints at the way papal dress and indeed the attire of many people in formal positions works. It not usually just about the shape and colour, but also the quality or materials used.

Being the pope is a bit like dressing for a wedding every day: even as a guest you wouldn’t turn up in your denims. You honour your hosts by wearing the best you possibly can.

The palette of the Pope

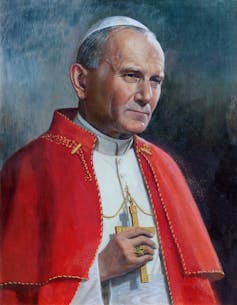

In the 21st century, popes have increasingly worn only white, now generally identified as the papal colour. But red is also a pope hue of choice – for example, John Paul II (1920-2005) usually wore white, but he also wore red capes and cloaks.

Benedict XVI (1927-2022) brought back the camauro – nicknamed the “Santa hat” – which is a red silk and velvet cap trimmed with ermine reserved for the pope’s use. The camauro goes back to at least the 12th century when it was related more closely to philosophers and teachers and the hat they wore, known as a pileus.

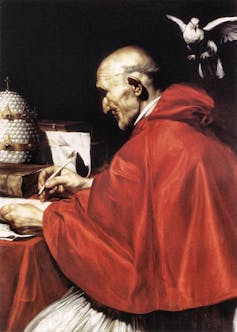

National Gallery of Ancient Art, Rome

Historically, portraits of senators, lawyers and academics often show them wearing red which is used to communicate a message of “official”.

Cardinals, the most senior clerics in the Roman Catholic Church next to the pope, wear red precisely because it is a papal colour and their power (or more accurately, influence) derives entirely from the pope.

Pope Paul II (1417-1471) tried to ensure quality over quantity when, amid shortages, he officially reserved the very best red dye for himself and his cardinals.

As a result of the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, trade from the eastern Mediterranean was disrupted. This meant that the supply of red dye kermes – which derives from the galls produced by parasitic wasps on oak trees indigenous to the Mediterranean basin and eastern Continent – was severely curtailed.

It was not until the middle of the 16th century that cochineal – which comes from parasitic insects on prickly pear cactuses – became available in Europe because of Spanish and Portuguese expansion into South America.

Whatever the dye, papal quality is also communicated by fabrics which hold unparalleled depths of hue: silk, not cotton or linen, alpaca not ordinary wool.

Renata Sedmakova/Shutterstock

Historians know from 13th century sources that popes have always worn white next to their skin (though from at least the 15th century their socks have been red).

White represents Christlike purity, innocence and charity, while red symbolises compassion and the pope’s willingness to sacrifice himself for his people.

In ancient Rome, red was the colour of imperial power whereas white was associated specifically with the city. So, the papal colours represent the pope’s universal significance as head of the Catholic church as well as his local position as Bishop of Rome.

Popes can also wear blue – Pope Nicholas V (1997-1455) particularly liked this colour. John Paul II, on one of his famous hiking trips, wore his white cassock under a padded blue jacket.

For papal fashion purposes, blue can stand in for red. In penitential seasons (Advent and Lent) or during periods of mourning, bright colours are not appropriate. But dip your bright red silks in a final dye bath of indigo and you get peacock (pavonazzo) which has the iridescence of the bird’s feathers.

Someone with the social conscience of Pope Francis I probably doesn’t give two hoots about what he wears. But as a Jesuit – one of the most highly educated, intellectual and thoughtful of all the groups in the Roman Catholic Church – he would understand the values of continuity and devotion communicated by both what he wears and how he wears it.

I would like to imagine, as he recovers from his respiratory infection, that he would be cheered up by high-tech mashups, such as this image of himself in a puffer coat – so long as they play within the rules of such a dignified man in such a venerable office.

Carol Richardson, Professor of Early Modern Art History, History of Art, The University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.