By Alister Doyle | Climate Correspondent

|

July 25, 2023 /Environment/ — Since it was set up in 1988, the U.N.’s prestigious panel of climate scientists has been led by men – a Swede, an Anglo-American, an Indian and a South Korean. That 35-year all-male run may end this week when governments pick a new chair for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) at a meeting in Nairobi from July 25-28. Two women – respected IPCC veterans Thelma Krug of Brazil and Debra Roberts of South Africa – are vying to win the votes of 195 governments. They would respectively be the first chair from South America or Africa. A win for a woman might help put the spotlight more firmly on developing nations and gender when the IPCC works out its next mammoth assessment of climate change, due to be published towards the end of this decade. Both the men candidates, Jim Skea of Britain and Jean-Pascal van Ypersele of Belgium, say they will promote women in climate science if they win. So women seem guaranteed a bigger role than their 30% share of IPCC authors in recent years.

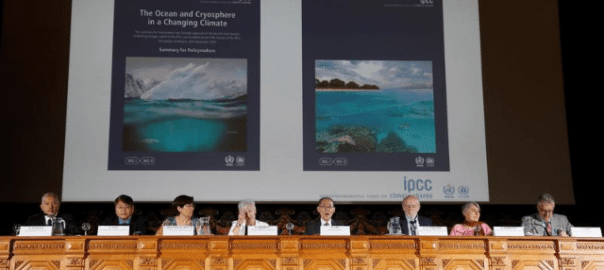

Chair of IPCC Hoesung Lee addresses a news conference as part of the 51st Session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in Monaco, September 25, 2019. REUTERS/Eric Gaillard |

|

But IPCC voting is notoriously hard to forecast – current chair Hoesung Lee, who beat van Ypersele in a runoff in 2015, was widely viewed as an outsider. “It impossible to predict. It’s not like the Eurovision song contest,” one scientist said, referring to the song-fest in which nations often favour their neighbours. Over the years, IPCC chairs have been generous in talking with me – starting at a conference in Moscow in 2002 when founding chair Bert Bolin of Sweden was dismayed that President Vladimir Putin gave a speech musing that climate change might benefit Russia. “Maybe it would be good and we could spend less on fur coats and other warm things,” Putin said. Bolin remarked ruefully: “We still have a lot of people to convince.”

Indah Lestari’s husband harvests sugarcane on his farm located near the food estate area in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia on June 20, 2023. He grows various kinds of fruits, vegetables, and tubers and sells them once they bear fruit. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Irene Barlian |

Rerooting food cropsThe hundreds of scientists who work with the IPCC – for free, alongside their day jobs – will study the physics of climate science, the worsening impacts of warming like record heatwaves, and solutions led by shifting away from fossil fuels. That includes how we can best continue to grow our food as weather patterns become more extreme and the global population rises. In Indonesia, the government wants to ensure food security with large-scale plantations known as “food estates”, growing crops including cassava, rice and corn. But it’s falling short – Michael Taylor visited Borneo where a forest was cleared for one such food estate, exposing what he describes as “a barren and eerie landscape that resembles the surface of the moon”. “Putting a cassava plantation in the middle of the jungle is not needed for security,” said Claudia Ringler, director of natural resources and resilience at the International Food Policy Research Network. Michael’s article about cassava kicks off a Context series called “Rerooted”, about the future of food on a warming planet. Look out for more – on subjects ranging from seaweed to millet – in coming months.

Covered solar dryer helps Shivraj Nishad ensure that dried flowers are free of contaminants like dust or bird droppings. It is especially helpful during monsoon months when most flower crops go wasted. Kanpur, India, June 27, 2023. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Bhasker Tripathi |

Solar flower powerThe IPCC, meanwhile, has said that coal use will have to be phased out entirely by 2050 – unless new technologies emerge to clean up emissions – to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times. Even in India, which is ramping up coal output to meet rising energy demand, banks are reluctant to finance newly auctioned mines because of the long-term risks that no one will want coal-generated electricity. Many other mines are awaiting finance as banks balk at climate and legal risks, as reported by Context‘s Roli Srivastava. |