Eleni Braat, Utrecht University and Ben de Jong, Leiden University

I was naked, tied to a hard chair with handcuffs. Three or four burly fellows in uniform are standing around me, one of them behind me with a truncheon… ‘Sie sind ein Verräter! [You are a traitor!],’ they snap.

These are the words of double agent “M”, who operated for the Dutch security service and the CIA against the East German Stasi for 22 years. In early 1985, it appeared that the Stasi may have uncovered his deception – and his true loyalty to the west. He was in East Berlin at the time and the men had rudely awoken M around 4am. Still in pyjamas, he was taken from the safe house where he was staying for debriefing sessions with his Stasi handlers to a van with darkened windows that transported him, under armed guard, to a prison.

They told him he was in the Untersuchungshaftanstalt (pre-trial detention center) Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, a notorious site during the cold war under the control of the Ministry of State Security (Stasi). M was forced to undergo a degrading and extremely painful cavity inspection, before being taken – still naked – to an interrogation room.

His captors intimidated him by pouring cold water over him from a bucket until the afternoon. They taunted him constantly, saying things like “You betrayed Marxism-Leninism” and “You are a CIA agent”. Yet M said he felt strangely reassured because these accusations were not specific – they were meant to provoke him. In other words, his interrogators seemed to lack proof.

We interviewed M extensively between 2019 and 2021 about his career as a spy during the cold war. He told us about his life as a “double agent” and how, in the end, he was abandoned by the masters he had served. We checked and cross-referenced his account and our research has been peer-reviewed and published in the International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. But it is hard to know the full truth when it comes to the secretive world of espionage, so we have tried to highlight those areas which are impossible to verify.

It’s important to underline just how rare it is for a former secret service agent to open up and talk on the record about their experiences. M gave us a truly unique insight into the secret workings of three different intelligence agencies. He spoke about issues he hadn’t even told his wife about.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

M’s spying career began in the second half of the 1960s when the Dutch security service, the BVD (Binnenlandse Veiligheidsdienst) – the predecessor of the present-day AIVD (Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst) – recruited him. He was working for a Dutch multinational that we have agreed not to name. That career would go on to provide excellent cover for his clandestine work, as it involved a lot of international travel.

M worked for the Dutch service for many years and subsequently for the CIA. The Americans were keen to use him when they learned he had also been recruited by the foreign intelligence arm of the Stasi – the renowned Hauptverwaltung (Chief Administration) A, known by its acronym HVA.

Over a period of more than 20 years, from the late 1960s until the end of the cold war, the HVA considered M their agent and he gave the East Germans information – much of it acquired through the multinational he worked for. But throughout this time, his primary loyalty was to the Dutch service and the CIA. From the perspective of the East Germans, M was indeed a traitor.

After seeing the evidence he provided to us, we believe his account of working against the Stasi is credible.

Listen to Eleni Braat and Ben de Jong talk about M’s life in an episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast.

A double-cross?

M’s motive in sharing his story stems from his desire to learn more about certain episodes from his spying career. He wants to find out, in particular, why his East German handlers, whom he had managed to deceive so successfully for so many years, suddenly seemed to turn against him in the mid-1980s.

It transpired that the humiliating interrogation was in fact a mock arrest led by Stasi handlers to test his mettle. But the episode planted a seed of doubt in M’s mind about whether the Stasi was on to him. A seed that would grow over the years to become an obsession. He would go on to believe that he had been betrayed.

According to M, only “treason” within the CIA could explain it – that a mole within the American intelligence service had betrayed him as a double agent to the Soviet KGB. During the cold war, the KGB, of course, worked very closely with the Stasi. On several occasions, M discussed the possibility that someone like Aldrich Ames, a notorious KGB mole inside the CIA between 1985 and 1994, was responsible for betraying him.

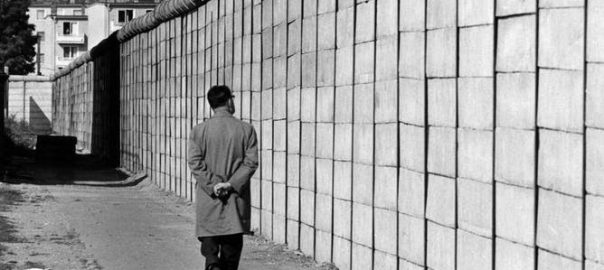

In all six of our interviews, M emphasised the distinctive nature of his relationships with the three different services he dealt with. His two long-time Stasi handlers were known to him as Wolfgang and Heinz. M’s meetings with them often took place in East Berlin, and sometimes in other venues in the Eastern Bloc such as Bulgaria or Yugoslavia. M could easily make such trips behind the Iron Curtain without raising suspicions.

Finding the CIA mole

By 1985, M was a seasoned double agent and seemingly getting on very well with his Stasi handlers, Wolfgang and Heinz. Nothing, therefore, had prepared him for the interrogation in the Hohenschönhausen prison.

While M spoke eagerly of the excitement and disillusionment he felt as a result of his spying career, he initially was reluctant to talk about this traumatising “mock arrest”. In the end, however, he told us about it in great detail – something he had never done before, not even to his wife of many years. He told us:

It was early spring and pretty cold. Their behaviour was rough, to say the least. After they have taken you in, they examine you. You are ordered to undress completely. All body openings are being inspected rather roughly. They threw me in a prison cell, and after a while they took me out again. Naked through the corridors on my way to the interrogation room. The corridors were lit. And if somebody would arrive from the opposite direction, they would push your face against the wall… It was overwhelming, to put it mildly.

He added: “You become totally demoralised. You can’t do anything and you are absolutely powerless. They rob you, as it were, of your identity and take away every shred of humanity.” Mentally, he recited the mantra: “Keep denying, do not give in. Keep insisting that as a foreigner you devoted yourself to the good cause, to socialism…”

Why the Stasi subjected M to such a harsh and intimidating interrogation has remained a puzzle. Was there a suspicion on the part of the HVA, based on a lead from a KGB mole in the CIA? Or was it just a way for the East Germans to test his mental resilience, to check if they could count on him in a stressful situation? In later years, he would ask himself these questions repeatedly. The possibility of treason from within the CIA became an obsession.

Either way, the interrogation ended suddenly and bizarrely. Wolfgang and Heinz entered the room unexpectedly and approached him in the most cordial manner: “Congratulations! You passed the test, you are now one of us!”

M was untied from his chair, handed back his clothes and taken to a room to freshen up. He was then taken to another safe house where he was given an award: a Golden Distinguished Service Medal of the National People’s Army (Verdienstmedaille der Nationalen Volksarmee).

Ben De Jong, Author provided

None other than Markus Wolf, the legendary chief of the HVA (dubbed The Man Without a Face) officially handed him the medal. Wolf had arrived at the safe house in a Volvo, the favourite car of high officials in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), escorted by motors at the front and rear.

“We shook hands,” M told us. “I found him a very friendly, amicable man… At a certain point, he told me: ‘You did important work for us’, but he did not go into specifics.” When M wanted to bring up his earlier unpleasant experience in the prison, Wolf cut him off by saying: “We will not discuss it.”

The meeting with Wolf lasted about an hour. A strange detail is that Wolf apparently put strawberry jam in his tea. As a young man during the Nazi period, Wolf had lived in exile in Russia, where this is a common habit.

The mock arrest and meeting with Wolf were unsettling for M, as he often said during our interviews. The day has clearly left a deep impression on him:

I was mentally put off-balance, I couldn’t wrap my mind around it. Even though the medal from the chief of the HVA flattered my ego, it also contributed to mixed feelings. I was a double agent after all, I was also a traitor.

‘I was a soldier in the cold war’

Our research focuses on the relationship between intelligence services and their agents – and in particular, how signs of gratitude and trust affect this relationship.

The case of M is illuminating because it allows for comparisons between the behaviour of three different secret services towards the same agent. We see the varying degrees of gratitude and recognition that the Dutch security service, the CIA and the Stasi showed for M’s work, from personal attention and verbal expressions of gratitude to material gifts.

Clearly, M felt a strong ideological commitment to the west and had no moral qualms about betraying the Stasi. As he put it: “I did not consider myself as someone who was deceiving others. I was a soldier in the cold war.”

The CIA was instructing M in techniques the Americans used to recruit KGB intelligence officers who might know about penetrations inside the US intelligence community. This operation started in 1987, amid investigations into the “1985 losses” the FBI and the CIA had suffered during a wave of arrests among their agents in the USSR. Potential approaches of KGB officers were preceded by psychological assessments that could estimate their willingness to collaborate.

M was tasked by the CIA to analyse the behaviour of his East German handlers using these techniques. The operation, codenamed RACKETEER by the CIA, used the Personality Assessment System designed by the agency’s former star psychologist John Gittinger. The CIA instructed M to observe the behaviour of Wolfgang and Heinz because the Stasi and KGB collaborated closely.

Paradoxically, M bonded most with these two handlers that he was deceiving. Their meetings always took place behind the Iron Curtain and the two East Germans showed their appreciation for M’s work on numerous occasions. In between debriefings, they drank Georgian cognac with him, covered his expenses without much ado, took him for day trips and copious dinners in restaurants and accompanied him on visits to nightclubs in East Berlin and elsewhere. “We visited nightclubs or a museum in Leipzig, we went for rides… In Budapest we went to those hot baths on [Margaret Island].”

M has fond memories of the time he spent with his two Stasi companions, who addressed him with the informal “du” [you] in German:

They were good at giving presents. I had once bought a very nice book of fairy tales for myself in Denmark, and sometime later they gave me a similar book as a present. I received medals from them, whereas the BVD never gave me a medal or another sign of recognition, not even a ballpoint. At another meeting with Wolfgang and Heinz in the East, I received all kinds of special treats because I had gotten married six months earlier [in 1970].

One of the wedding gifts the Stasi gave him was an exquisite Bohemian crystal vase. They would even take M to toy shops where – at their expense – he could indulge his love for model trains. But with the BVD, it was different. Years later, when M got access to his BVD file, he found that at the time of his marriage, the service decided M would not be given a special present as he had been declaring too many expenses.

At a meeting in East Berlin shortly after his marriage, Wolfgang and Heinz asked M if he would appreciate a Frauenbesuch (a female visitor) on a particular evening. This surprised him. “I think the HVA wanted to find out: ‘How far will this agent go? What does he accept? How honest is he?’ Also, I would have put myself in a vulnerable position with the East Germans by saying yes.” In other words, M always had to be on guard in his dealings with the Stasi, even with his “friends” Wolfgang and Heinz.

New publications on the Stasi and the HVA started coming out in large numbers after the collapse of the GDR. With these new resources, M managed to trace the full names of what he believes to be his handlers, Wolfgang Koch and Heinz Nötzelmann. But his attempts to contact them were unsuccessful. The full names of Wolfgang and Heinz also appear in publications by the Stasi archives in Berlin, and a man said to be Koch even appears in a photograph in a book on the history of the Stasi.

Recruited by ‘Herr Gerber’

We were able to corroborate some, but not all of M’s claims about his spying career with documents from his personal files. M has avidly documented everything that happened to him, including correspondence, some of it fairly recent, with the three services. He also has the medal he officially received from the Stasi. In addition, we applied to the AIVD for access to M’s file, but our request was refused several times.

M was from a working-class background. After completing his secondary education in the Netherlands, he spent a year at a high school in the US which proved to be a formative experience. After obtaining a degree in engineering, he fulfilled his military service with the Dutch army and began his career at the large multinational. By then, he had already become familiarised with the practice of espionage, including its basic techniques, during his military service.

Iain Masterton / Alamy Stock Photo

Through his career in several European, African and Asian countries, M acquired many international contacts and was able easily to obtain information that was of interest to intelligence services. Initially, Dutch security tasked him with infiltrating local extremist organisations, both on the left and right, that were part of international networks. However, in 1981, they handed him over to the CIA because his spying activities had become too international for the national orbit of the Dutch security service.

In the winter of 1967-68, during an internship in Israel that was part of his studies, a somewhat older German-speaking man introducing himself as “Gerber” approached M and invited him for dinner. Gerber showed a keen interest in M’s background, such as the year he had spent at an American high school and – a rather unusual topic for a casual conversation among strangers – Israeli nuclear developments in the Negev desert.

Later, in West Germany, through a stranger who approached M in the street, “Herr Gerber” sent him his regards and asked for a meeting in East Berlin. M’s Dutch handlers correctly interpreted this approach as a recruiting attempt by the Stasi, and encouraged him to respond favourably. He became a double agent: by successfully pretending to be a Stasi agent, M would acquire valuable information on the personalities of his Stasi handlers for the Dutch service.

He also gathered information on the type of short-wave radio receivers, communication devices and codes the East Germans used, as well as the kind of intelligence they wanted him to acquire in the many different countries where he was stationed for his job. To his Stasi contacts, M explained his willingness to work with them as a consequence of the defects he saw in western capitalism, in particular the many forms of social and racial injustice he had personally observed.

When he became engaged to his future wife, M confided during an intimate dinner at a restaurant that he was working as an agent against the Stasi. His wife did not know the details of his spying, but she was aware of the many trips he made behind the Iron Curtain to meet his Stasi handlers. Indeed, she told us she could see for herself how M was always completely exhausted when he came back home from these meetings, having spent several days in the company of Wolfgang and Heinz.

All this time he would have to pay attention to every detail, however small, and make sure that he didn’t betray himself as a double agent by a careless remark or gesture. On a few occasions, his wife even played an operational role. Several times after M’s return from the Eastern Bloc, she was the one who made a phone call to transmit a pre-arranged coded message to the CIA, implying that M had come back safely.

Trust and gratitude

Our research has found that agents and double agents desire a relationship with their handlers that involves trust and gratitude, not just one based on financial compensation. This desire can be explained by the often-hostile environment an agent operates in, which involves distrust, fear, danger and social isolation.

But suddenly, in 1988, M’s relationship with Wolfgang and Heinz cooled. In his debriefings with the CIA, M had given elaborate descriptions of the personalities of both – mentioning Wolfgang’s brown eyes as a striking physical attribute. Then, during a subsequent meeting, Wolfgang said out of the blue: “You don’t like brown eyes, do you?” M was shocked. His shock was even greater because Wolfgang said this in English, in the precise wording M had used in his CIA debriefing. M told us he barely managed to control his emotions:

I could no longer trust anyone… I had to be constantly alert and wary… To remain in this position over such a long period of time requires much stamina… There is a line of appreciation, trust, but also of abandonment… You are being used as a pawn by something amorphous, by an entity that you cannot enter. No, they will approach you… You are appreciated for your efforts, but [these services] remain a dark cloud that you cannot enter.

This episode ushered in a period when both Wolfgang and Heinz became more distant. The male bonding and the toasting were over and their body language had changed. M kept wondering if he had made some error or, again, whether a CIA mole had blown his cover.

Finally, in early 1990 – less than a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall – the HVA cancelled a meeting abruptly, and that concluded his career as a double agent. No gunshots, no bomb explosion, no Stasi dungeon. It wasn’t like the movies. A meeting was simply cancelled, and the door on his spying career slammed shut.

Shutterstock/carlofornitano

The end of the friendship with his East German handlers and “the insecurity and threat” that it generated, in M’s words, had a considerable impact on his wellbeing. It contributed, in his view, to his ensuing depression and nervous breakdown in the early 1990s for which he would receive psychiatric treatment. “You do not have any colleagues in espionage,” he said.

You are left entirely to your own devices. [The separation from my handlers] was really a turning point. Until then I was engaged in all kinds of geopolitical developments, I was right on top of them. I had interesting contacts. And then suddenly, all this ended, and I was sitting at home. That was a shock.

Enjoying the excitement

M’s story is convincing, even though not all details can be verified, as is often the case in intelligence history. The existing literature on intelligence history allows us to confirm parts of M’s story or assess the likelihood of certain episodes by comparing them with other known cases. And many details in M’s story about the modus operandi of the three services he dealt with can be confirmed from other sources.

Most importantly, recent correspondence between M and the Dutch AIVD about access to his file shows that he had been their agent. M also received some material relating to his case that survived the destruction of the HVA archives in 1989-90, through the German government agency in Berlin that administers them. He allowed us to see and check all of these documents. They prove that he had also been a Stasi agent.

The Stasi supplied M with Dutch, American, Swiss, British and West German passports that enabled him to travel inconspicuously under different names, especially when he was on his way to a rendezvous with his Stasi handlers. He also communicated with them through dead drops (pre-arranged sites where both parties could leave messages, money or documentation) and written or oral messages. M received messages from the Stasi through short-wave radio transmissions in code from a so-called numbers station in the GDR. These messages consisted of numbers read out monotonously according to a pre-arranged transmission schedule.

Shutterstock/Chintung Lee

Sometimes M would also exchange messages and material the East Germans were interested in by way of fleeting meetings in hotel lobbies with East German diplomats. Such meetings are called “brush passes” in spy-speak.

M clearly enjoyed the role he played behind the scenes during the cold war and the excitement that came with it – a common phenomenon in the intelligence world. It is also clear, however, that traumatic memories from that period continue to be a considerable burden to him. His obsessive interest in spies, agents and treason is striking. His former CIA handler (who M managed to get back in touch with in recent years) advised him in an email: “Let it go, man, let it go.” But this was clearly to no avail.

Abandoned after all those years

Traumatic memories that come back to haunt people many years later are a common phenomenon for war veterans. M feels the CIA abandoned him after the cold war, when he was no longer useful for them. He feels the BVD did the same when they handed him over to the CIA in 1981, renouncing any further responsibility towards him.

When M finally got access to his BVD file in the mid-2010s, he was not allowed to make notes or copies. To his amazement, he came across a document he had completely forgotten about which he had signed himself. It concerned his transfer to the CIA in 1981. It stated that from then on the BVD would no longer bear any responsibility for him. He told us: “The BVD abandoned me completely… after all those years that I had risked my life…” This document came to play a role in his dealings with the Dutch service after his spying career had ended.

In 2016, M’s emotional problems became acute, and he spent a night in an hospital emergency ward. This episode coincided with his approaching the AIVD about receiving access to his file. He asked for their assistance in getting treatment from an agency “with experience in treating the emotional burdens of a long-time double agent”. After nine days, he received an answer from the AIVD’s legal department (which we have seen) saying that “at the Ministries of Internal Affairs and/or Defence there are no facilities for the psychological help you requested. I advise you to contact your GP, so he/she can put you in touch with a regular therapist.”

This lack of cooperation on the part of the AIVD intensified M’s feelings of bitterness. He told us:

In that world, they just fuck you. This is not how they should treat people that have worked for them for so many years. After all, I went behind the Iron Curtain for them on many occasions.

In the end, with a bit of luck, M managed to find help at an institution that specialises in the treatment of war veterans. This treatment is still ongoing. Without a doubt, it was also his bitter feelings that made him eager to share his fascinating life story with us.

For you: more from our Insights series:

-

How China combined authoritarianism with capitalism to create a new communism

-

Embracing uncertainty: what Kenyan herders can teach us about living in a volatile world

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Eleni Braat, Associate professor of international history, Utrecht University and Ben de Jong, Research Fellow, Leiden University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.