|

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is everywhere. Thanks to a lack of red tape, it’s transforming our homes, economies and cultures – from ChatGPT and virtual DJs, to facial recognition and predictive policing tools. However, the rise of AI has also come at a significant cost. As we’ve discussed in recent weeks, AI often undermines our privacy, entrenches societal biases, and creates opaque systems that lack accountability. A visitor wears virtual reality goggles at the World Artificial Intelligence Cannes Festival (WAICF) in Cannes, France, February 10, 2023. REUTERS/Eric Gaillard |

So, how can we harness the beneficial potentials of AI without facilitating harm?Over the past few years, EU policymakers have been trying to develop legislation that will do exactly that. The AI Act aims to “ensure that Europeans can benefit from new technologies” so long as they uphold “Union values, fundamental rights and principles.” If passed, the ambitious legislation would become the world’s first AI law passed by a major regulator and, like GDPR, could quickly become a global standard. In fact, its international impact is already being felt, with lawmakers in Brazil citing the draft legislation as inspiration for their recent AI policy. But promoting innovation, encouraging economic growth and upholding fundamental rights is a complex and difficult task. And unfortunately, in its current form, the AI Acts looks likely to disappoint nearly everyone. Staff members from Qian Ji Data Co take photos of the villagers for a facial data collection project, which would serve for developing artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technology, in Jia county, Henan province, China March 20, 2019. REUTERS/Cate Cadell |

What is the EU AI Act?The AI Act will regulate the development, marketing and deployment of artificial intelligence within the EU. It categorises AI tools into four risk categories, from the unacceptable to those deemed to pose a minimal risk, and regulates them accordingly. Technology considered to have an unacceptable risk will be banned. These will likely include social scoring algorithms like those in China, as well as certain facial recognition and other real-time biometric identification systems. At the other end of the scale, systems with limited or minimal risks like email spam filters and chatbots will face barely any restrictions. Perhaps the most significant and contentious classification are those deemed to be ‘high risk.’ While not prohibited, manufacturers of these tools will be forced to comply with a number of requirements before selling their products. The constraints aim to diminish the risk of algorithmic errors, bias and discrimination while encouraging transparency and accountability. Technologies likely to fit into this category will likely include automated hiring tools, benefit scoring algorithms, and border management tools. However, there’s still a lot still to be decided.

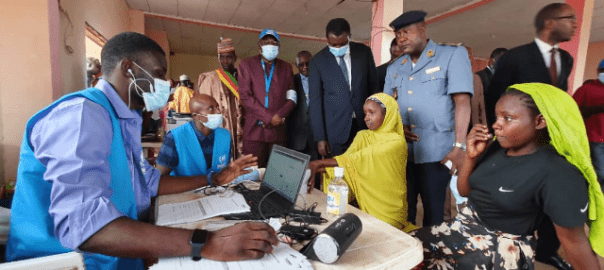

Officials supervise the delivery of digital ID cards to refugees from the Central African Republic at the Gado-Badzere camp in Cameroon. June 26, 2022. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees/ Handout via Thomson Reuters Foundation |

Too far, or not far enough?Given the scope of the Act, it’s unsurprising the Act has drawn criticism from industry and civil society alike. On the one hand, businesses have claimed the broad definition of AI could stifle growth, with one group claiming the Act will cost the EU’s economy €31 billion over five years. Meanwhile, rights groups have pointed out the many limitations of the legislation in protecting fundamental rights. Of particular concern are the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. As a group of civil society organisations recently wrote: “Whilst the proposed AI Act prohibits some uses of AI, it does not prevent some of the most harmful uses of AI in migration and border control, despite the potential for irreversible harm. However, promoting innovation and protecting peoples’ rights aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Just last week, a group of investors representing over €1.5 trillion published a letter also demanding greater protections for human rights. In it, they called for extending the list of prohibited AI practices and pointed out significant shortcomings in the Act’s potential to fully eliminate the risks associated with facial recognition and predictive policing tools.

An illustration photo shows a woman holding a national identity card, an eye on a phone screen, a man in a mask and a life vest, and a surveillance tower on a background of newspaper clippings and barbed wire. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Nura Ali |

What’s next for the AI Act?The AI Act has faced sustained scrutiny from politicians, industry, and civil society since first being introduced in April 2021. And it’s fair to say a consensus is yet to be established, with reports emerging last week that even the definition of AI is yet to be settled. The Act will likely face a committee vote at the end of March, with plenary votes then scheduled for April. At this point, MEPs will work to negotiate the final terms of the legislation. Expect heated discussions, major amendments and the continuation of disputes over how best to protect fundamental rights while promoting innovation and investment. Any views expressed in this newsletter are those of the author and not of Context or the Thomson Reuters Foundation. |