Alan Rice, University of Central Lancashire and Jack Hepworth, University of Oxford

From the earliest arrivals of what would become Preston’s “Windrush generation”, the status of the Caribbean diaspora was hotly contested in this post-industrial Lancashire town, as elsewhere. Discrimination and prejudice dogged the daily lives of people from the Caribbean who made their home here.

In 1955, the pages of the Lancashire Evening Post hosted intense debates about whether a “colour bar” existed in the town. And segregation still endured two decades later, when the national Race Relations Board challenged discrimination at Preston Dockers’ Labour Club, where black people were being denied service. Because of its status as a private premises, the club won the case in 1975. New legislation would be required to overturn such discrimination.

Amid this febrile atmosphere, Preston’s growing Caribbean community organised independently, forming social networks through church congregations, sports teams and, latterly, community institutions.

Yet today, many of these inspiring stories of community strength and individual endeavour remain little acknowledged. As Clinton Smith, chair of the Preston Black History Group, put it:

A great deal has been written about Windrush – but much of the information was southern-based and related to large conurbations.

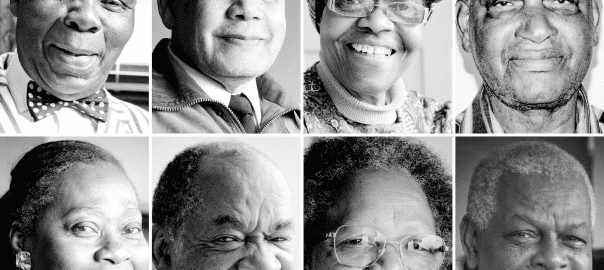

Seeking to address this “big city bias” regarding the Windrush story as it approached the 75th anniversary, members of the group – together with the Institute for Black Atlantic Research at the University of Central Lancashire – interviewed and photographed 11 proud black Prestonians in depth about their experiences as migrants arriving and putting down deep roots in this provincial town.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

Their recollections – collected in the ebook England is My Home: Windrush Lives in Lancashire and extracted here – offer a fascinating insight into the fears and hopes, the triumphs and ongoing challenges that Preston’s Caribbean community has experienced over the past 75 years.

At the heart of these memories are vital communal spaces such as the Jalgos club – founded in a house on London Road in 1962 by Jamaicans unified by a love of cricket – and the Caribbean Club, which opened in Kent Street a decade later and proved particularly popular with the Dominican community. In 1974, Preston’s island communities united to stage the town’s first Caribbean Carnival, a tradition that continues today.

Church, carnival and cricket: the three pillars of this vibrant local community – built in Preston by proud members of its Windrush generation.

Sylius Toussaint

I remember my paternal grandma had two posters in her house that my cousin had put on the wall. One said: “Belfast, the city without a slum.” Pure government propaganda. And the other was a scene of apprentices working in a factory, and it said: “Britain today is the land of opportunity for youth.” I will never ever forget that. I wish I still had that poster.

My aunt said to me: “Sylius, why don’t you go to England? You could work, study and whatever it is.” So I paid my passage and came – and here I’ve been for the last 60-plus years.

I left Dominica on May 29 and arrived in Barbados the following day. But while we were there, we discovered the boat to England was overbooked. So we were sent on an aircraft from Barbados to Bermuda, Bermuda to Newfoundland, then Newfoundland to Ireland.

My first impression was of cottages and things in rural Ireland, and I said: “This looks poor.” When you are in the Caribbean, you hear of England, you hear of Ireland and Europe, and you think it is affluent and rich. But then when you see this – really? That was the first surprise I had.

And when I finally landed in Preston, with its silly little two-up and two-down houses, I said: “Really? I thought there were no slums in this place! Two-up two-downs, outside toilet in the middle of winter …” And every house was smoking. “What’s this smoke?”

Preston has changed, wow. There were so many slums back then. And I thought winter [in England] was cold but sunny – but when a whole week went by and I never saw the sun, I said: “What have I come to?”

So, why am I happy for coming here? Because I’ve been able to help others. Initially it was my mum and other siblings. I arrived and within almost a year, I sent for [my wife] Bridgette and, before long, her brother and my sister. My sister lives down in London with her children … and some (not all) of them say:

Uncle Sylius, that’s the best thing you’ve done, sent for my mum, because I’m glad I’m here in England and life is so much better than if it was in the Caribbean.

Economically, England is a big boy whereas Dominica is still a child. So most of what I do [to help] is out there. And I say thank God I’ve been able to come here, and that me coming here has been of benefit to so many people.

If you ask me what are the industries in Preston, I don’t know. But the place seems to be getting on quite well. What surprises me is how the university has just expanded. From being an industrial town, we’ve become a university town now.

The two-by-twos have gone, and there aren’t any slums in Preston now. Of course, there are houses that may be neglected, but you watch the news and see the kind of housing that people have to live in in London and so on. We are not bad in Preston.

Joanett Hue

When I reached Preston, it was night. I had been driving from London and I saw all these houses and said to myself: “These look like a certain part of the ghetto in Jamaica – the area I don’t go in.” Honestly, I couldn’t believe it. Looking at the houses, I said: “My god, it’s no different.”

At that time, we lived in Avenham [in central Preston], the flats. When I went in there, [my husband] Joe said: “This is where I’m living – this is the kitchen, this is the bathroom.”

I couldn’t believe it. The house I was coming from [in Jamaica] was a seven-bedroom house, five bathrooms. Honestly, when my husband said this is where we would be living … I went into the bathroom and I cried, I cried. I said: “Why did I leave my house to come here?”

When I woke up in the morning, there were hailstones, it was raining. I couldn’t take it anymore. But then I just said to myself: “Well, I have my husband and when you come to Rome, you do as the Romans do.”

Vincent Skerritt

When I came to Preston, I was out of work for about three or four weeks, and I lived in Ribbleton Lane with a friend I got to know when I came here. Then I got a job at Leyland Motors.

Black people couldn’t get certain jobs. They couldn’t join the union and often it was much more physical work, like in the foundry, knocking iron and the engine blocks and the rest of it. I worked there for about ten months. It was purely nights, and I couldn’t handle the night work. Sometimes you would get up and wouldn’t know what day it was.

There used to be Teddy Boys here in Preston when I first arrived. Fortunately, I never experienced or got involved with them.

But there used to be a strategy with us. We would come to the Red Lion pub and drink the ale, but we also used to buy a bottle of Guinness and have a newspaper, and wrap it up nicely in it. So you walk in with a bottle knowing that if you’re attacked, you have something to defend yourself.

Some people used to have a little piece of iron metal, wrapped up nicely in a newspaper and you carry it under your arm. Fortunately, I never had to use it.

Glyne Greenidge

I got to 17 and had to find work [in Preston]. My mum’s husband wasn’t a very nice man, and my mum suffered all the way. I’m the oldest of seven children, so my stepdad kind of forced me out to work as soon as he could.

It was mainly in the cotton mills – that was the main work going in those days. The money wasn’t good but the work was plentiful. You could walk the streets and see little firms here or there. You could go in and ask them if there were any jobs going.

I worked nights, mainly. And I met one of my best friends, an English lad called Kevin. He’s died now. He became my best friend. We went out to get a drink, and we were similar ages – maybe he was like a year older than me. That’s where I started getting some racist remarks, and it upset me. And my mate Kevin sat me down and said: “Don’t let that worry you. If you let that worry you, you’re going to have a hard life. Ignore it.”

He was my mentor, you could say. Maybe he didn’t realise it. We’d become such good friends that we used to sleep at each other’s houses. He would come to my mum’s house, and we would stay there. We worked nights together and we would have dinner with my mum and whatever. And I would stay sometimes at his mum’s house and sleep. His dad had died so it was just him and his mum.

We built up that relationship, you know? And that was fantastic. Best friend I ever had. They were Irish people, you see. He didn’t look down on anybody. He saw people as people. So he never used any racist remarks. In fact, he would defend me and help me out at times if I felt low and depressed.

Later, I was working with this fellow, he was a fitter. He came from the docks because Aerospace was taking on a lot of people at the time, and a lot came from the docks when they were shedding labour. And me and him got on okay – in fact, we were good friends.

But one day we were having a debate or discussion and this racism came up. I can’t remember now word for word, but I said to Frank: “But you aren’t a racist then, are you?” And he said: “Yes, I am.”

I was a bit taken aback about that. But then again, I never let that spoil our relationship because we were friends, you know.

Gladstone Afflick

Preston is home – I’ve lived here since 1960. I left Jamaica on the July 28th and arrived in Preston on the 30th – a Sunday. To be honest, I’ve never, never thought of going anywhere else.

To me, Preston has come a heck of a long way since the sixties. Things have changed that much. As I said to one young guy in our Jalgos club only about a fortnight ago; he was shouting his mouth off and I said to him: “Don’t come in here and try to tell us what to do. You should be thinking how you are going to thank us for making it possible for you to walk and enter buildings in Preston [without fear of violence or abuse].”

There was about five pubs along Friargate, before the ring road. All them pubs along there, no black guys could go in them. One was called the Waterloo – that used to be the National Front headquarters. You could get into a fight seven days a week if you wanted, just by walking into town.

I’ve always done what I can for my community since I arrived in this country. For instance, we have the Jalgos Sports & Social Club – I was the person who dragged 11 fellows together to form a cricket team. And I dragged 11 guys together to found a football team, too.

When we started the football team, you’d be running and [opponents] would say: “Give the ball to the monkey because they don’t know what to do with it.” Those were statements made every Saturday.

But then, when they realised we were beating them, they stopped talking. You get the meaning? We were playing while they were talking, and they started trying to play but they couldn’t beat us. So in the long run … what did I call it? To overcome adversity. Yeah. We overcome it that way, by not arguing.

Jalgos is a community-based organisation – I am the chair of the club now. I say to people over and over, Jalgos is not only nationally known – we are internationally known. People in Jamaica know more about Jalgos than people in Preston.

I tried to unify, if that’s the correct word, the community. I said to them, irrespective of where you are from, first and foremost you are a West Indian. You can’t run away from that. You are a West Indian. Which island you come from is secondary. And if we think that way, I think we will achieve together what is desired by all.

Cherry McDonald

Sometimes I wonder, if I didn’t travel to England, what would my life be in Jamaica? Strangely, I always refer to Jamaica as home. I mean, I’ve been living here all these years but Jamaica is home. I don’t want to be disrespectful, but Jamaica is home.

I’ve got a good life here, though. Whatever I’ve achieved in life, I’ve achieved here in Britain. And I enjoy my life – me and my television. And if there’s something happening at Jalgos and they need my assistance, I come and help.

I’m ticking along nicely. I go for long walks, tend to the pots, go to church on Sunday in Longton, and read my bible at home.

However, I think Jalgos started going down when they banned smoking indoors. If I was a smoker, I would not be going outside to smoke a cigarette – in winter, anyway. The younger ones want to smoke there, and they don’t want anybody saying: “You can’t do that in here.”

It’s a shame really with this club, because we’ve had many, many happy occasions downstairs, before upstairs was made. Down here we used to have a jolly, jolly good time. My parents used to visit here and we’d have a wonderful time. My first daughter was married down here.

It is a shame when I look at this building now. The younger ones are not following in our footsteps. So that’s the beginning and the end of it.

Bridgette Toussaint

I didn’t want to go anywhere else but Preston. But sometimes, you have to know how to speak to the people here. When I speak nicely to them, they understand that this is a lady, she will respect me.

For example, in one job I did, a woman said to me: “Bridgette, I don’t understand, why did you leave your nice place and come here? Why do you have to come to steal our jobs?”

I said: “Steal your jobs? Because you’re lazy, that’s why they send for we black people to come to help to work. Because you’re lazy!”

Then she said: “Why don’t you go and dance with the monkeys in the zoo?”

And I said: “What? Where I come from, we’ve got cows, horses, donkeys, dogs – and snakes which are bad. So don’t you speak to me like that. If you are a white monkey, then go. There’s white monkeys – you can jump with them.”

Oh boy. Everybody said: “How dare she speak to you like that?” They were all for me and everybody was laughing at her, because she find herself to be stupid. I got up and said: “You can give but you cannot take, can you?”

But then she became my friend. That’s it. All you have to do is just calm down. She ended up being my best friend! Giving me a lot of things. I don’t really need it, but she was nice after.

Preston is not bad now. Not too good, but not bad. Where we are, we are happy. I would not go and retire to Dominica. I’ve got no reason.

David Coke

I’ve been back to Jamaica 11 times, and I’ve never had a bad experience. But I won’t go back to live there, because I have become so acquainted with the lifestyle I have in England.

I came here at 12 years of age, and got married at 22. But even before I married, I’d always said to my wife that I wouldn’t go back to Jamaica. And I said to my daddy more than once, and I said it to mum too – I thank God they had the vision to take us from Jamaica to here.

I’ve had an excellent experience in Preston. Anywhere I go in the world, I’m always wanting to come back to Preston.

I like the discipline in this country. I like its organisation. And I’ve heard my father say the same thing as well: there’s no better country than England. Yes, America may be more modern and faster, and you can progress in life there much quicker than you can in England. It’s true: I’ve been there and I’ve seen the accomplishment over a short period of time.

But I like the discipline here. I love the organisation. I know if I’ve got an appointment at eight o’clock, it’s eight o’clock – not ten minutes past eight as it is in Jamaica. It’s not perfect here and there’s a lot of terrible things happening in government. But as bad as it is, it’s better than where I come from.

Yes the sunshine in Jamaica is lovely, the food is lovely, you can get up in the night and walk naked in your house and you’re not shivering. It’s comfortable – in fact, too hot. I love that when I go back there.

But for me, Britain, England, is my home. I have enjoyed the 60-odd years that I have been here very much. I have no complaints at all. I’ve been to Australia, I’ve been to Africa, to Canada, and to the United States. No, it’s always back to England and back to Preston for me.

Alan Rice, Professor in English and American Studies, University of Central Lancashire and Jack Hepworth, Canon Murray Fellow in Irish History, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.