John Curtice, University of Strathclyde

The death of Queen Elizabeth II after 70 years on the throne has, of course, been met with widespread sadness and mourning. For most people in Britain, she is the only monarch they have known. Yet, inevitably, the mourning of her passing will be followed by a discussion about the future of the monarchy as an institution. After all, much has changed since 1951.

Although it may have provided the head of state for over a thousand years, in a modern democracy like Britain the monarchy will need to retain public consent if it is to survive.

Over the past 30 years, the British Social Attitudes survey conducted by the National Centre for Social Research has regularly asked how important or unimportant it is for Britain to have a monarchy. The results shed some light on how attitudes have shifted over the decades and what might make a difference to public opinion in future.

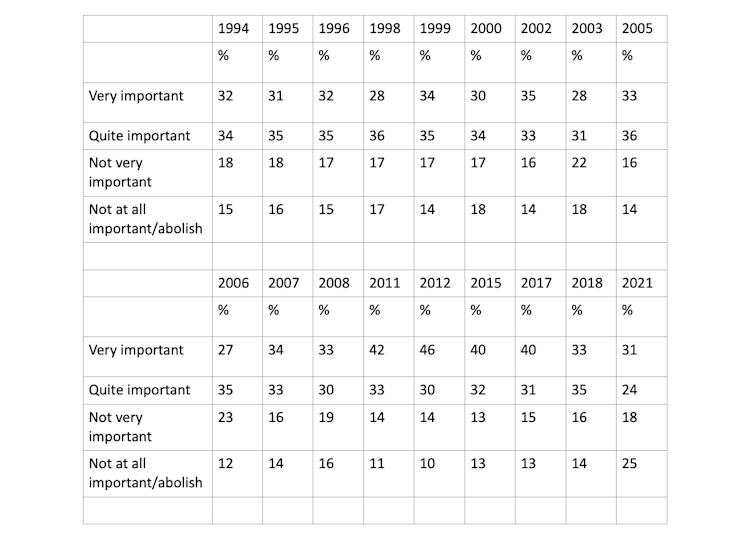

Since 1994, having a monarchy has consistently been regarded as “very” or “quite” important by a majority. In 1994, two-thirds (66%) expressed that view and, in most years since, the result has often (albeit not always) been much the same. To that extent, the foundations of public consent for the monarchy have appeared to be remarkably solid and stable.

That said, when this question was asked on the first British Social Attitudes survey in 1983, there was even more support. As many as 65% had said it was “very important” for Britain to have a monarchy, while another 21% said it was “quite important”.

Back then, almost everyone appeared to be a “monarchist”. Indeed, the issue seemed so uncontroversial that we stopped asking the question in the survey. It simply did not seem worth it.

That changed in 1992. This was, as the Queen herself admitted, an “annus horribilis”. The carefully crafted portrayal of the monarchy as a “royal family” was rocked by the decision of three of her children to separate or divorce their partners, including, most controversially, the then heir to the throne, Prince Charles, and his popular wife, Diana, Princess of Wales.

The question on the monarchy was reinstated and we have ended up with a more nuanced picture ever since. Support for the monarchy has never returned to the level first recorded in 1983.

Attitudes change in response to events

Despite the overall stability since 1994, there have been rises and falls in the perceived importance of the monarchy that have further illustrated how public attitudes can shift in response to specific events.

The eventual divorce of Charles and Diana in 1996 and the death of Diana in a car accident the following summer saw the proportion that thought it was “very important” to have a monarchy fall to below 30% for the first time. The royal family’s initial response to Diana’s death had attracted considerable criticism and this was considered a very difficult moment for the institution.

Trends in attitudes towards the monarchy, 1994-2021

British Social Attitudes, Author provided

The standing of the monarchy then improved again following the Queen’s first-ever trip to the Republic of Ireland in 2011 – a visit that did much to improve the sometimes troubled relationship between the UK and its nearest neighbour.

Then, the following year (the year of her Diamond Jubilee) the Queen bridged the community divide in Northern Ireland by shaking the hand of former IRA commander, Martin McGuinness. In the British Social Attitudes survey that followed, two in five or more said it was “very important” to have a monarchy, perhaps because it was seen to be proving its diplomatic worth.

More recently the royal family has hit stormy waters once again. First, serious allegations against Prince Andrew led to his withdrawal from public life. Meanwhile, by 2020 a serious rift had opened up between the royal family on the one hand and Prince Charles’s younger son, Harry, and his charismatic American wife Meghan on the other. Harry and Meghan eventually opted to withdraw from royal duties and reside in the US.

These most recent developments have seemingly seen support for the monarchy reach a new low. In the latest survey, only 55% said it was “very” or “quite” important for Britain to have a monarchy, while those who say it is either “not at all important” or that it should be abolished has reached a quarter (25%) for the first time.

It does therefore seem that the successes and problems of the royal family affect how much people value the institution. King Charles has inherited the crown at a time when support for the institution of the monarchy has fallen to a new low.

Meanwhile, until now people’s views will have been influenced by their perceptions of the late Queen herself. Future public support for the monarchy may well rest heavily on King Charles’s ability to prove a worthy successor.

Charles III meets gen Z

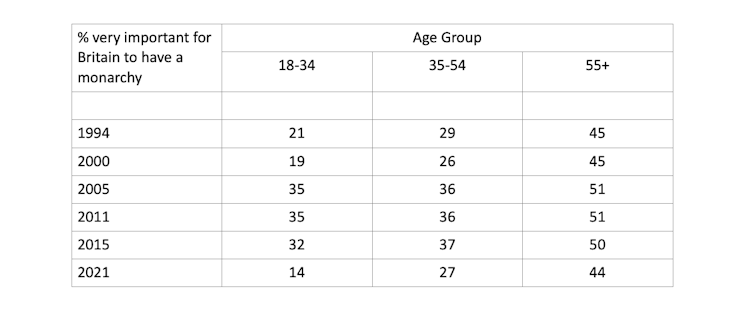

Moreover, the monarchy would appear to face a potential achilles heel. Results from the survey over the years show that younger people are less likely than older people to say that it is “very important” that Britain has a monarchy.

Indeed, just 14% of under 35-year-olds take that view, compared with 44% of those aged 55 and over. This suggests there is a risk that support for the monarchy will decline as today’s older generation is replaced by younger cohorts.

Attitudes towards the monarchy by age, 1994-2021

British Social Attitudes, Author provided

However, this pattern is not new. The gap between younger and older people was much the same in 1994 as it is now, even though the younger people of 30 years ago are now middle-aged, and the ranks of today’s older people comprise many who were then middle-aged.

The relative stability of the age gap reflects the fact that the older they become, the more likely people are to feel it is “very important” to have a monarchy. In 1994, only 22% of those born in the 1960s felt that it was “very important” to have a monarchy, ten points below 32% figure among the population as a whole. Now, in contrast, 38% are of this view, seven points above the proportion among all adults.

Perhaps the success of the monarchy lies in its ability to offer people a sense of stability in what is otherwise an ever-changing world.![]()

John Curtice, Senior Research Fellow, National Centre for Social Research, and Professor of Politics, University of Strathclyde

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.