Phil Tomlinson, University of Bath; Andrew Burlinson, University of East Anglia; Catherine Waddams, University of East Anglia; Donald Hirsch, Loughborough University; Jean-Philippe Serbera, Sheffield Hallam University; Jim Watson, UCL; Jonquil Lowe, The Open University, and Steven McCabe, Birmingham City University

UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has just launched the biggest package of tax cuts in half a century. This will involve around £45bn of reductions for people and businesses by 2027 – 50% more than anticipated before the mini-budget announcement.

Amid the worst cost of living crisis in a generation, Liz Truss’s government wants to boost growth and usher in “a new era” for Britain. It is targeting a 2.5% annual growth rate via a three-pronged approach of reforming the supply side of the economy, taking a “responsible approach” to public finances and cutting taxes.

The tax cut element was trailed heavily during the recent Tory leadership contest, but now that we have some firm details, our expert panel offers their views on Kwarteng’s plan.

Gambling on growth

Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, Deputy Director Centre for Governance, Regulation and Industrial Strategy, University of Bath

The UK economy is stagnant. Prices continue to rise, while consumer and business confidence plummets. In response, the UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has presented a mini-budget which he says will “go for growth”.

The headline tax and stamp duty cuts, alongside recent energy price caps, are aimed at easing household and business finances. Then there are plans for regional investment zones designed to offer tax incentives and fewer regulations.

All of this is being funded by huge levels of public borrowing in the hope of boosting consumer spending, stimulating enterprise and staving off recession. The government is gambling on economic growth to pay off its enormous debts.

And it’s quite a gamble. The stamp duty cut for example, will only fuel an already inflated housing market. And “enterprise zones” do not guarantee new investment.

In fact, this mini budget is worryingly reminiscent of another Conservative gamble from 50 years ago. In 1972, the then chancellor Anthony Barber, announced massive tax cuts and higher public borrowing in a “dash for growth” at a time of high inflation and rising unemployment.

The “Barber boom” is now a textbook case of how not to engage in fiscal largesse. It led to a temporary uplift in growth, and then a debilitating hangover of even higher inflation, a sterling crisis and Britain eventually having to go cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund.

Today, the markets are already nervous. A hard Brexit has exacerbated the UK’s record trade deficit, with the value of sterling recently dropping to its lowest level against the US dollar since 1985. This raises import inflation, and the Bank of England has begun to respond aggressively by raising interest rates, hitting borrowers and business investment, and raising the costs of servicing government debt.

There remains a strong case for a fiscal policy targeted at promoting new business investment, infrastructure, skills and public services. Unfortunately, this “trickle down” mini-budget is unlikely to deliver that elusive long-term growth.

Personal finance

Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance, The Open University

The government is giving big tax cuts to the better-off, but offering little to lower-income households. The recent 1.25% rise in national insurance is being reversed, and income tax will be cut in April 2023, with the basic rate falling to 19% (currently 20%) and the top 45% rate for the highest earners abolished.

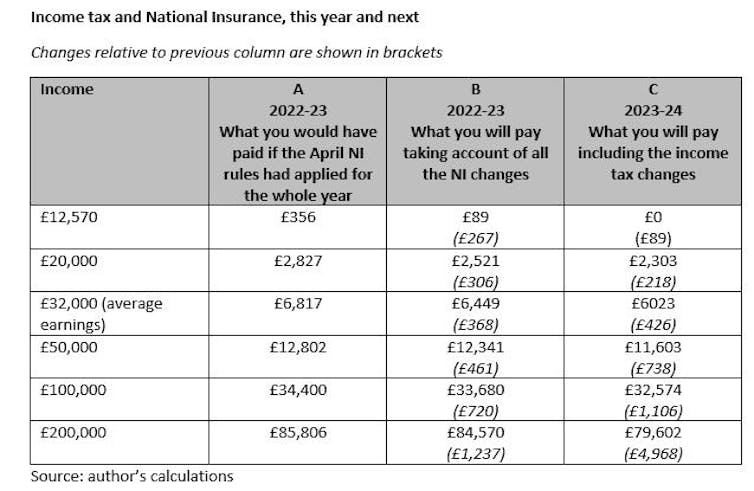

As the table below shows, these changes mean take-home pay for someone on average earnings of around £32,000 will increase by £368 this year and then go up by another £426 next year. The poorest households, earning too little to pay NI or income tax, do not benefit at all.

Author provided, Author provided

The government argues that these tax cuts will stimulate the economy, increasing jobs and incomes for all. But recent research was the latest to find no evidence that this approach works, and suggests instead that tax cuts for the rich serve to increase inequality, which is already much higher in the UK than it was 40 years ago.

The government also says it will “make work pay” for lower-income households by cutting the benefits for those unemployed or working part-time if they do not, without good reason, make sufficient effort to either take on work or work longer. This could be especially hard on people (mainly women) who are dovetailing work with caring for children or older relatives.

A major concern is that the personal tax cuts will stoke spending by the better off, fuelling inflation. Current inflation rates have led to the Bank of England recently ratcheting the base rate up another 0.5%, which is bad news if you are one of the 2 million people on a variable-rate or tracker mortgage, or if your fixed-rate mortgage is due to end soon, or if you are a buyer taking out a new mortgage.

Meanwhile, first-time buyers especially may benefit from a substantial increase in the thresholds at which stamp duty starts to be paid (in England), provided this does not simply fuel house price inflation.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has called the chancellor’s package of tax cuts unsustainable. And if the government’s growth-plan fails, households need to brace themselves for tax increases – or another bout of painful austerity – further down the track.

Vulnerable households

Donald Hirsch, Professor of Social Policy, Loughborough University

Kwarteng claims the government is embarking on a “new approach for a new era”. And this mini-budget certainly shifts the Treasury’s emphasis away from the past three years, when the main goal was protecting those hit hardest by the pandemic and rising energy costs.

But the new approach will provide little comfort to low income families who have faced blow after blow to their finances over the past year. There was a £1,000 cut in universal credit payments last October, a similar loss in April (as a result of those payments rising much more slowly than prices), and a further £500 fuel price increase due next month.

Even taking into account the planned cost of living support, a typical family on benefits is about £1,400 worse off this year than last.

By freezing the new energy cap, the government has invested massively in preventing the situation from becoming far worse for everyone. But in doing so, it has missed the opportunity to focus on those for whom £1,400 is simply unaffordable.

Those households will face severe hardship this winter. The cuts in national insurance and income tax will provide them with little (about £135 a year for those working full time on the minimum wage) or nothing (zero benefit for those not working or earning less than £12,500).

Kwarteng could have chosen to reassure those receiving universal credit that payments would match this month’s double-digit inflation rate when uprated next April. Instead he went for “reforms”, tightening conditions for claimants, and punishing those who do not meet them. The reassurance was saved for the 1% of the population who earn over £150,000, and will now keep an extra 5% of anything they make over this amount.

Last week, the US president Joe Biden declared that trickle-down economics had “never worked”. In the UK’s “new era”, it is clearly being given another chance.

Energy crisis

Andrew Burlinson, Lecturer in Energy Economics, University of East Anglia, and Catherine Waddams, Professor of Economic Regulation, Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia

Top of the agenda for the chancellor’s mini-budget was what he referred to as “the issue most worrying British people today: the cost of energy”. Kwarteng restated the government’s energy price guarantee plan which sets an average cost for typical household energy usage at £2,500 a year, still twice the levels at the same time last year.

With so many households facing severe hardship this winter, a wide-ranging package including some form of cap was needed, and the immediate relief will be welcomed. But unfortunately, a general cap with extra relief for some households is inadequately targeted and too short term.

It will dampen the incentive to respond to higher energy prices for those who can afford alternative generation, such as solar panels and better insulation – a crucial contribution to net zero targets. Meanwhile, households that are unable to respond to such incentives, especially prepayment consumers, remain vulnerable to unsustainable financial pressure.

The government has ignored calls for a social tariff to provide further help for such households. Government action to boost installation of renewables and energy efficiency technologies could also lift millions of households out of fuel poverty, save lives and improve the health and financial wellbeing of households.

Social tariffs and energy efficiency schemes could be paid for in the short-term by a windfall tax on oil and gas companies, a popular approach among the public, and through general taxation in the medium to long term. A more sustained and effective strategy on prices and demand is needed to deliver climate goals and energy justice.

Investment in energy

Jim Watson, Professor of Energy Policy and Director of the Institute of Sustainable Resources, University College London (UCL)

Kwarteng’s growth plan provided an opportunity to fill a gaping hole in the government’s response to the energy price crisis. A large-scale programme of investment in home energy efficiency is badly needed to bring down bills, lower gas demand, improve health and help reach our climate targets. It could also reduce the amount of government borrowing required for the energy price cap.

But the government has decided not to take up that opportunity. A smaller commitment to existing schemes delivered by energy suppliers was announced instead. While this is not trivial and will target those on low incomes, the scale of the energy and climate change crises means that it is simply not up to the job.

With this in mind, we will ultimately need to move away from fossil fuels for most purposes. But Kwarteng’s plan continues a pattern of mixed signals from the government on this issue.

It restates the commitment to investment in one of the UK’s most successful low carbon technologies (offshore wind) as well as more uncertain, longer-term options such as nuclear power and hydrogen. There is also a surprising and positive commitment to reduce planning restrictions for onshore wind, which is one of the cheapest forms of electricity.

Shutterstock/David Falconer

But this support comes alongside new oil and gas licenses and an end to the ban on fracking. Neither of these strategies are likely to have a significant impact on energy prices, particularly in the short term, as is sorely needed. There are also serious questions about their compatibility with our climate change targets.

The plan includes an increase in the estimated revenue from the windfall tax on oil and gas, from £5 billion to £7.7 billion in this financial year. This tax could have been extended further to help pay for the energy price cap, and to boost investment in low carbon infrastructure.

Business impact

Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute for Design, Economic Acceleration & Sustainability (IDEAS), Birmingham City University

Kwarteng’s decision to scrap the planned increase in corporation tax, which had been due to rise from 19% to 25%, will be welcomed by businesses. As the chancellor claimed, this should make the UK a more attractive place to invest and result in a jobs and tax-take increase. It also means investors in companies retain more profits.

Whether this provides sufficient incentive for additional investment is questionable, however. On the other hand, a removal of the cap on fees for certain specialised investment schemes may encourage more funds for innovation and product development.

Kwarteng intends to underpin growth through 40 investment zones throughout England that will offer special tax breaks and reduced planning and environmental regulation for business. Kwarteng claims this will “unleash the power of the private sector”.

We’ve seen this sort of intervention before in the 1980s and again in 2012, with mixed results. Kwarteng’s investment zones are also unlikely to solve the huge social and economic problems we face.

Rather than Boris Johnson’s fabled objective of “levelling up”, they risk merely encouraging existing businesses to relocate to enjoy tax breaks. This will not recreate the thousands of well-paid manufacturing jobs lost when traditional industries closed in the 1980s.

Overall, many businesses will be disappointed by what was announced. There will be continued concerns about business closures and redundancies accelerating, with the consequential loss of much-needed tax revenue to pay off the ever-increasing public debt.

What businesses needed from the government was genuinely radical intervention to stimulate manufacturing. What we got will not produce the growth we need. Look at the immediate market reaction, as measured by the falling pound.

Property market

Jean-Philippe Serbera, Senior Lecturer in Banking And Financial Markets, Sheffield Hallam University

A permanent reduction in stamp duty, at a time when the property market has rarely been so strong, is perhaps one of the stranger aspects of the mini-budget. Kwarteng has raised the threshold for payment from £300,000 to £425,000 for first time buyers and to £250,000 for all other residential purchases.

The motive behind the change must be to further support the housing market by reducing overall costs for those trying to get onto the housing ladder, while also benefiting property investors.

On the face of it though, it seems ill-timed. Property prices are already at record levels, and it will cost the government billions of pounds. However, with the Bank of England raising interest rates, and inflation squeezing personal savings, it may be a way for the government to temporarily postpone a crash in UK house prices that is bound to happen – and sooner rather than later.

Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, Deputy Director Centre for Governance, Regulation and Industrial Strategy (CGR&IS), University of Bath; Andrew Burlinson, Lecturer in Energy Economics, University of East Anglia; Catherine Waddams, Emeritus Professor of Economic Regulation, Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia; Donald Hirsch, Professor of Social Policy, Loughborough University; Jean-Philippe Serbera, Senior Lecturer in Banking And Financial Markets, Sheffield Hallam University; Jim Watson, Professor of Energy Policy and Director of the Institute of Sustainable Resources, UCL; Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance, The Open University, and Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute for Design, Economic Acceleration & Sustainability (IDEAS), Birmingham City University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.